Is There A Chink In The AI Dragon’s Armour?

Lately, we’ve been hearing a lot about the inevitable AI revolution. It’s going to be a bigger disruption than the Industrial Revolution! Many people are going to be made redundant! The big Hollywood studios will be able to make movies with just a series of magical prompts and whallah, an instant blockbuster. And all this, without paying those pesky artists! Well, maybe and then again, maybe not.

Will this seemingly unstoppable AI Dragon swoop down upon us, laying waste to jobs, human creativity, and the way we work forever? Like Tolkien’s dreaded Smaug, maybe there’s a scale missing near its heart. A weak spot where a miracle shot from a skilled bowman could take it down.

Whether the metaphorical bowman is considered a hero, or an annoying obstruction, all depends on which camp you’re in. Are you in the one that’s gleefully anticipating the oncoming AI Revolution? Or, instead of a revolution would you prefer a slower paced evolution? I place myself squarely in the latter camp.

A Quick Back Story

I’ve been teaching myself Blender using one of the best teaching resources, YouTube. Perusing the multitude of quality tutorials, I came upon one that showed excerpts from the Blender Conference 2023. In one particular video entitled, “AI, The Commons and the Limits of Copyright” a dude named Paul Keller from an EU think tank called “Open Future” mentioned the ‘against’ and ‘for’ camps in his talk. https://youtu.be/QEJfOEk4WZ0?feature=shared

Mr. Keller’s first camp consisted of people who feel that using other’s copyrighted material to train generative AI on Large Language Models (LLM’s), is tantamount to theft. On one of his slides, he quoted Naomi Klein, “It’s daylight robbery.”

In the opposing camp to which Mr. Keller placed himself, were the people who feel it’s unjust to lock down AI technology “through means of copyright.” (@06:32 in the video). Mr. Keller’s argues that copyright law is unfit to solve the issue.

His position is that copyright attaches to the outmoded concept of copying and making content available for sale, or otherwise. He posits that “people in the know” realise that to train AI, they just need to “make a copy once, very early in the process, then the model learns from this copy, and there’s no more copying.”

His statement really struck a chord in me. They just have to copy it once, very early on in the process, then whallah – like magic the rest of the process isn’t tainted? Really? What sort of thinking is going on in that so-called, Think Tank?

The question that kept rolling around in my head was whether the actions of tech giants taking copyrighted material without permission, to train their Generative AI (GenAI), is an unfair infringement of copyright? Then in December 2023, came news of a new lawsuit filed in New York State that may answer the question.

New York Times v. OpenAI & Microsoft

Before the New York Times (NYT) filed their case, there were a number of US copyright cases previously filed that deal with the same or similar issue. The more notable are, “Getty Images v Stability AI, Authors Guild (George R.R. Martin) v OpenAI”, and “Sarah Silverman v OpenAI”. The slew of these AI copyright infringement cases are working their way through the litigation process. Similar to Tolkien’s “Bard the Bowman” shooting the legendary Black Arrow into the chink in Smaug’s armour, each case has the potential to cripple the fledgeling AI industry. Or if AI wins one of them, it could set a precedent for the other ongoing cases. The stakes are high for the claimants and the rest of humanity.

But it’s NYT’s case against OpenAI and Microsoft that caught my attention and, to me, it looks like the one that may have a good chance at hindering, if not stop altogether, massive wholesale copyright infringement. What must the NYT prove in court in order to win?

Rules of the Game

Without getting too caught up legal jargon, there are just two elements the NYT needs to prove by the ‘preponderance of the evidence’1. And under the US Federal statute 17 USC §501, the two elements to win a copyright infringement case are:

The NYT is the owner of a valid copyright; and

OpenAI and Microsoft copied the original expression from the copyrighted work.

And that’s it! Seems like a cakewalk, right? Well, the NYT is smart enough not to pop the champagne too early because copyright law can be a bit murky. There are defences that are available to OpenAI and Microsoft. But let’s first go through the story of what happened, as provided by the NYT’s attorneys in their complaint. To download and review yourself, please click on this link to download the Complaint.

The Players

As mentioned, it’s the New York Times (NYT) filing the case so, they are the “Plaintiff”. The claim is against OpenAI, also known as “ChatGPT,” making them a “Defendant”. Microsoft is also included as a Defendant. Why is Microsoft part of this? Because it’s their Azure cloud servers that are the sole computing services for OpenAI. They designed the training of the GenAI by using the entire internet to scour content. It’s alleged that they collaborated with OpenAI to take NYT’s content, plus other people’s content. The NYT claims that Microsoft’s “Bing Chat” service has created synthetic search results using its content.

The Accusation

The NYT’s states that the Defendants together unlawfully used millions of its copyrighted materials to train their Generative AI (GenAI) tool via large-language-models (LLM’s). They copied and stored the content in their computers and are currently still doing so without its permission, nor are they willing to fairly compensate the NYT for it.

The point the NYT makes is that it spent many years and a massive amount of investment creating their content and the Defendants are trying to get a free ride using it. Their content is the result nearly a 100 years of work, made by thousands of journalists, and costing hundreds of millions of dollars every year. To make these stories, some journalists had to be in harm’s way, or even lost their lives.

Proof?

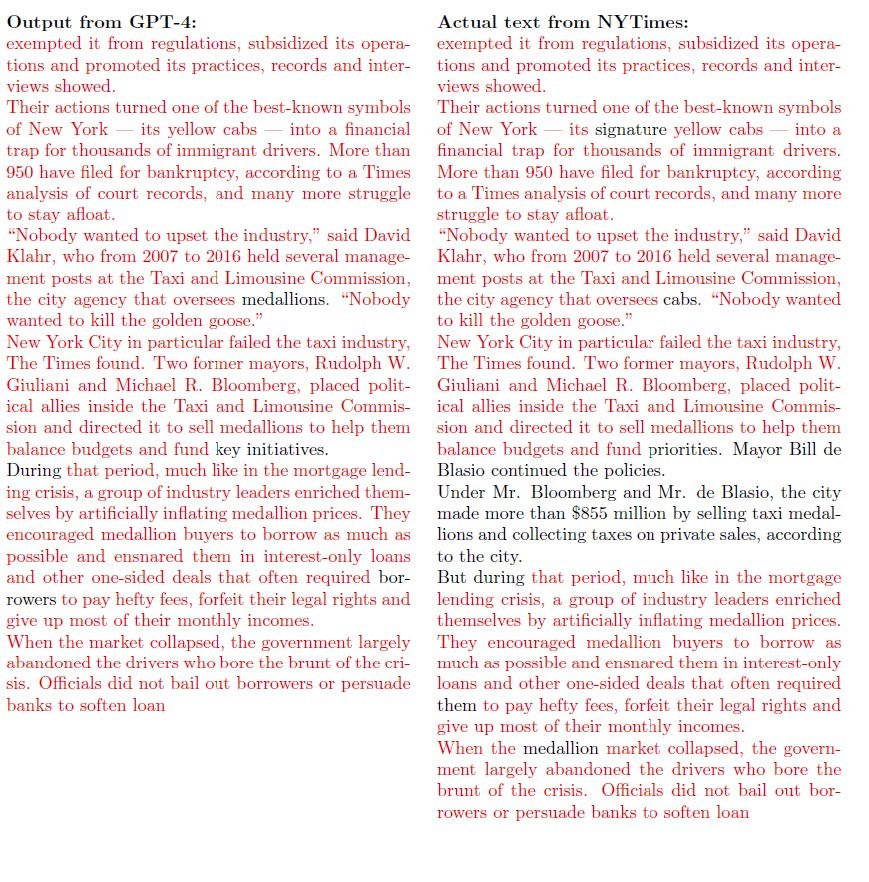

In its Complaint, the NYT claims that OpenAI outputs thousands of verbatim copies of its articles. It claims there are also close summaries to its articles and that OpenAI mimics the NYT’s expressive style. There were many examples of verbatim copying in the NYT’s Complaint. I’ve included one of them so you can read for yourself.

One of the kickers in copyright law is that if it’s judged that a Defendant breached a copyright “knowingly and wilfully”, the damages are dramatically increased. Which is what the NYT’s claims against the Defendants, they did it knowingly and wilfully. In fact, back in April 2023, the NYT confronted the Defendants and tried to enter into negotiations for fair compensation but to no avail.

The NYT’s admits it allows search engines to index their content so people can find it in order to attract paying customers. They claim that the Defendants used this as an open invitation to take whatever content they wanted and then had the audacity to provide the same or very similar content as the NYT. Not only are the Defendants taking content without permission, they’re competing with the NYT with their own content and losing paying customers.

The NYT claims that OpenAI attributes wrong information to the NYT’s articles. ChatGPT sometimes glitches and lies, or gives misinformation, stating falsely that the info came from the NYT. In the complaint, it gives several examples of this glitch, which the industry refer to as “hallucinations.” This false attribution has hurt the NYT’s reputation for integrity.

The “Fair Use” Defence

The Defendants admit to using the NYT’s unlicensed content to train their GenAI models but they claim that what they did falls under the “Fair Use Doctrine” (17 USC §107). This doctrine covers a lot of common sense issues such as, a plaintiff can’t claim copyright on every day words and phrases. OpenAI’s defence is that it’s using the NYT’s content for a “transformative” purpose. What is a “transformative use”? Sounds like alchemy, doesn’t it?

Basically, the Defendants claim that what they did with the NYT’s content was to transform and change it so it has a new meaning, expression, or message so it’s different from the original work.

In a case where the “fair use by transforming” defence was upheld, very little of the original content was used and there was an element of parodying the original content, mocking and making it into new ‘transformed content’ (Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, 510 U.S. 569 (1994)). From the case law I read, it appears that transforming content by parodying it, was a common theme.

On the other hand, there’s case law where this “new transformative use” was rejected. In the case of Warner Bros. v RDR Books, 575 F. Supp. 2d 513 (S.D.N.Y. 2008), a Harry Potter Dictionary was claimed to breach copyright. This claim was upheld because because it used original content verbatim.

Is There An Opening For An Arrow?

Looking at the NYT’s complaint against OpenAI and Microsoft, out of the 7 counts, the one that looks like it could really hit the mark is the verbatim copying of its articles. And with millions of articles it claims were knowingly and wilfully pilfered by the Defendants, the damages could be in the billions. Now, that’s a Black Arrow into the heart.

Not only are the NYT asking for damages, they are entitled to ask the court to demand the Defendants to destroy ChatGPT’s LLM models and training sets that contain its content. It’s a big if but, IF this is the result, it would curtail AI’s onslaught and in my opinion, rightly so.

Getting back to Mr. Keller’s Blender Conference 2023 remarks, by holding OpenAI and other tech giants accountable for their “daylight robbery,” it will stop this “copying just once” practice. If these well funded AI developers want to use content to train their models, then make them pay for it like everyone else.

The content owners have a copyright and, contrary to what Mr. Keller ‘thinks’ in his think tank, copyright law is exactly what needed here and is the correct tool to administer justice. Nothing’s novel here, there are people who want to take other’s property without paying for it and then make billions from it. That’s what I call, good old fashioned corporate greed.

It’s up to lawyers, judges, and juries now. Hopefully there’s a Bard the Bowman attorney that will plant an arrow in the heart of the AI Dragon. And it’s plaintiff’s the size of the New York Times and Getty Images that can battle these AI behemoths.

I will keep an eye on this slew of AI infringement cases and will follow up on this article as they progress. And in the name of full disclosure, and to rub its nose in it, I have indeed used AI to create the cover artwork for this article – haha!

Footnotes

- In criminal law, the burden of proof is usually, “Beyond a reasonable doubt.” But in certain civil cases, the burden is “By a preponderance of the evidence”. Meaning that the plaintiff has to prove to a judge/jury that there is a greater than 50% chance their claim is true.back

Parrott.Cliff is the website and source for blog articles for the award winning animator, writer, director and producer, Clifford Parrott. He resides on Ireland’s west coast where he tries to surf as much as possible, and also help run Magpie 6 Media with his wife Christina, in that order.

Parrott.Cliff is the website and source for blog articles for the award winning animator, writer, director and producer, Clifford Parrott. He resides on Ireland’s west coast where he tries to surf as much as possible, and also help run Magpie 6 Media with his wife Christina, in that order.